When I returned to writing for pay, I first tried to sell a story about the Christmas Bird Count to some publishers. “Good job,” they wrote, “but this is better suited for a magazine article than a book!”

I reframed my piece and submitted it to Bird Watcher’s Digest. It appeared in the November-December issue in 2007. I still very much like this topic, and I’d like to write more about Frank Chapman one day.

You can read a form of my manuscript here…

Saving the Birds on Christmas Day

It was a Christmas tradition, and it was a brutal one. They called it the “side hunt.”

Groups of men and boys, town and country folk alike, would meet in December, oftentimes on Christmas Day, side up into teams, and head into the woods to shoot everything they could. It was a practice that continued well into the last century.

These hunters were not killing to put food on their tables for Christmas dinner. Nor were they hunting in order to feed their families through a long, harsh winter. The object of their side hunt was to see whose team returned with the biggest load of dead birds and animals.

Yet they were not the first to hunt winged creatures in early winter. For centuries, birds in the British Isles and in Europe were targeted as prey during the darkest days of the year. Scholars offer many reasons why. Perhaps the birds served as a sacrifice at Winter Solstice. Earlier people killed animals and birds and made offerings of them, asking the Sun to bring longer days to warm the earth and make way for spring.

Others, including folk in Ireland, Wales and England, kept another custom that survived into the 1900s. They believed that wrens, among the smallest of songbirds, were symbols of misfortune. The merry wren, with its upturned tail and distinctive chitter, was to be hunted down and killed at Christmastime.

On Boxing Day, December 26, bands of young men and boys called “wrenboys” hunted the tiny birds, pinned them to poles, and paraded them from house to house. “The Wren, The Wren, the king of all birds,” they sang in jest, as they demanded food and drink. More times than not, they got their reward.

But even as the wrenboys held to their winter ritual, things were beginning to change. In 1900, an American ornithologist named Frank Chapman proposed a new type of hunt. Why not simply count the birds? A lifelong bird lover, Chapman worked at the American Museum of Natural History in New York. “Ornithology,” the study of birds, was a brand-new specialty among the museum’s scientists who studied the animal kingdom.

“A new kind of Christmas side hunt, in the form of a Christmas bird-census,” Chapman wrote in Bird-Lore magazine. Chapman edited this early journal about birds, which reached readers across North America. He urged his readers to spend a portion of Christmas Day outdoors “with the birds” by counting each and every one.

No one seems to know how Chapman came upon the idea of a Christmas Bird Count. Perhaps Chapman was tired of seeing all kinds of women , from socialites to shopgirls, wearing hats adorned with plumes of near-extinct egrets and herons – and sometimes entire birds. Or maybe Chapman knew that mass killing of birds like the passenger pigeon for food and sport meant certain loss of a species once as common as today’s sparrow.

And so on December 25, 1900, 27 eager birders in the United States and Canada answered Chapman’s call. This new breed of huntsman counted birds along the chilly waters of Scotch Lake, New Brunswick, in the barren fields of North Freedom, Wisconsin, and beside the sea in Pacific Grove, California. On that single Christmas Day, they counted 90 species and a grand total of 18,500 birds.

One century later, more than 50,000 birdwatchers across the Americas take part in the Christmas Bird Count. Now they hope to count as many as 70 million birds. They report their findings to the National Audubon Society, which protects and promotes the welfare of birds and their habitats across the United States.

The Audubon Society organized the Bird Count by “circles,” that is, areas both land and water 15 miles in diameter. Ardent bird lovers visit one or more of 2000 circles found across the Americas from the Artic Circle in the north to Tierra del Fuego along the southern tip of South America. The Bird Count season runs from December 14 through January 5.

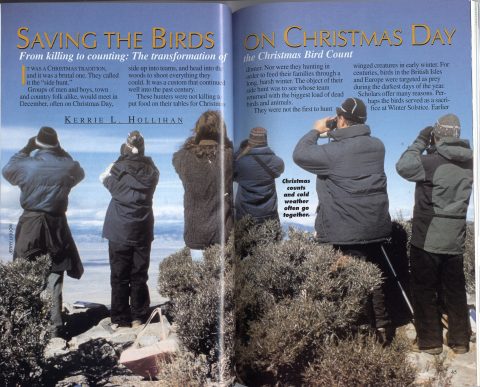

From one midnight until the next at any time during those 23 days, observers search for all the birds in their circles. They try to cover each one. Whether on foot, on hands and knees, in boats and canoes, by snowmobile or hanging out in trees, avid birders within each circle log each and every bird they see.

Birders make careful notes about their location, the time of day, and the weather. They also include how much effort it takes to spot a particular bird. Some birdwatchers trek miles and miles in darkness and daylight, in rain, snow, sleet or sun, as they make their counts. Others run their checklists right at the feeders in their own back yards.

Depending on the weather or terrain, birdwatchers wear boots, running shoes, snowshoes, swimming shoes, skis or sandals. They spot snowy owls in Bangor, Maine, snowy egrets in El Paso, Texas, snow buntings in the Quivira Refuge, Kansas, and snow geese in Macon, Georgia. Sometimes, their days’ work rewards them with a surprise – as when birders discovered a white ibis in the Arizona desert and a turkey vulture in downtown Pittsburgh.

The birders return home at the end of their trek tired, hungry and happy. Like the wren boys before them, they look forward to sharing a meal and a Christmas cookie or two. Each group counts their totals and recounts the day’s events. Everyone celebrates when the tally includes a surprise species.

That first Christmas Bird Count of 1900, Chapman asked his readers to quickly mail their bird counts at the Post Office so that he could report them in the February 1901 Bird-Lore. Today, most of these reports take wing on the Internet to the Audubon Society. Data each season “are viewable to the public–and are in the database in preliminary form–well before the end of the winter,” says Geoff LaBaron, Christmas Bird Count director for the Audubon Society. The society reviews the data, writes articles and publishes the CBC summary issue of American Birds later in the year.

These vital reports help scientists to understand how bird populations rise and fall just as the birds finish flying to their winter homes. They can find out how birds change their homes from year to year and whether their numbers are growing. Moreover, scientists can find out how birds react to changes in habitat, the weather, disease and human activity.

Over many years, Frank Chapman took part in Christmas Bird Counts at his New Jersey home. Though Chapman wrote in detail about his work, he told nothing of his thoughts about the bird count or how he kept Christmas. But a book he wrote for families about feeding winter birds revealed him as both a scientist and a bird lover:

The twittering Juncos at our doorstep, the Nuthatches and Woodpeckers at our suet-baskets, the Chickadees that take food from our hands, are not only our welcome guests but our personal friends.

It is not only what we give them but what they give us, that should make us thankful for birds in winter.

As Chapman peeked out the window on frosty December mornings, did he know how big an impact his modest idea would have? No one can be sure. But we can be certain that Chapman’s Christmas Bird Count launched a big idea: Every child, woman and man, in everyday life, can become a citizen scientist.

What a wonderful gift for Christmas.

Author’s Note

Within five years of the first Christmas Bird-Census in 1900, fledgling Audubon societies in several states banded into a powerful association called the National Audubon Society. You can read more about the Christmas Bird Count (CBC) on the Audubon Society Website at https://www.audubon.org/conservation/science/christmas-bird-count. The society was one of many organizations founded by Americans in the late 1800s and 1900s to nurture our land and wildlife as a national treasure.

Famous Americans and ordinary scientists alike joined the growing conservation movement, including well-known Americans like Theodore Roosevelt, John D. Rockefeller and Rachel Carson. Others less well known – Margaret Murie, Ernest F. Coe and Gifford Pinchot – also cherished the out-of-doors and recognized that land and wildlife need protection and preservation.

They might not realize it, but every man, woman and child who takes part in the Christmas Bird Count (CBC) is an acknowledged citizen scientist. “Citizen science” is a modern term that describes the age-old practice of birdwatching combined with scientific evaluation of what birdwatchers find.

For amateur birders, this is good news. Professionals now recognize their work as a valued contribution to ornithology. The Audubon Society has partnered with Cornell University to create a website where birdwatchers can send their observations and learn more about birdwatching. Every time you send in your sightings, you help scientists to study the health and welfare of birds. As the Cornell Lab states on its website,

Every bird that is reported, regardless of its beauty or ubiquity, is important.

Every citizen scientist who submits data makes a difference!

To get started as a citizen scientist, go to https://www.audubon.org/conservation/science/christmas-bird-count.

For more information about the Irish wrenboys and their now-gentle way of celebrating Christmas, visit the Dingle Peninsula website at https://dingle-peninsula.ie/wren-s-day.html/

©Kerrie L. Hollihan 2021